Table of Contents

Chandra :: Photo Album :: MSH 15-52 :: June 24, 2021

Chandra :: Photo Album :: MSH 15-52 :: June 24, 2021

Motions of a remarkable cosmic structure have been measured for the first time, using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. The blast wave and debris from an exploded star are seen moving away from the explosion site and colliding with a wall of surrounding gas.

Astronomers estimate that light from the supernova explosion reached Earth about 1,700 years ago, or when the Mayan empire was flourishing and the Jin dynasty ruled China. However, by cosmic standards the supernova remnant formed by the explosion, called MSH 15-52, is one of the youngest in the Milky Way galaxy. The explosion also created an ultra-dense, magnetized star called a pulsar, which then blew a bubble of energetic particles, an X-ray-emitting nebula.

Since the explosion the supernova remnant — made of debris from the shattered star, plus the explosion’s blast wave — and the X-ray nebula have been changing as they expand outward into space. Notably, the supernova remnant and X-ray nebula now resemble the shape of fingers and a palm.

Previously, astronomers had released a full Chandra view of the “hand,” as shown in the main graphic. A new study is now reporting how quickly the supernova remnant associated with the hand is moving, as it strikes a cloud of gas called RCW 89. The inner edge of this cloud forms a gas wall located about 35 light years from the center of the explosion.

To track the motion the team used Chandra data from 2004, 2008, and then a combined image from observations taken in late 2017 and early 2018. These three epochs are shown in the inset of the main graphic.

Timelapse: 2004, 2008, 2018

The rectangle (fixed in space) highlights the motion of the explosion’s blast wave, which is located near one of the fingertips. This feature is moving at almost 9 million miles per hour. The fixed squares (seen in the images below) enclose clumps of magnesium and neon that likely formed in the star before it exploded and shot into space once the star blew up. Some of this explosion debris is moving at even faster speeds of more than 11 million miles per hour. A color version of the 2018 image shows the fingers in blue and green and the clumps of magnesium and neon in red and yellow.

While these are startling high speeds, they actually represent a slowing down of the remnant. Researchers estimate that to reach the farthest edge of RCW 89, material would have to travel on average at almost 30 million miles per hour. This estimate is based on the age of the supernova remnant and the distance between the center of the explosion and RCW 89. This difference in speed implies that the material has passed through a low-density cavity of gas and then been significantly decelerated by running into RCW 89.

The exploded star likely lost part or all of its outer layer of hydrogen gas in a wind, forming such a cavity, before exploding, as did the star that exploded to form the well-known supernova remnant Cassiopeia A (Cas A), which is much younger at an age of about 350 years.

About 30% of massive stars that collapse to form supernovas are of this type. The clumps of debris seen in the 1,700-year-old supernova remnant could be older versions of those seen in Cas A at optical wavelengths in terms of their initial speeds and densities. This means that these two objects may have the same underlying source for their explosions, which is likely related to how stars with stripped hydrogen layers explode. However, astronomers do not understand the details of this yet and will continue to study this possibility.

A paper describing these results appeared in the June 1, 2020, issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters, and a preprint is available online. The authors of the study are Kazimierz Borkowski, Stephen Reynolds, and William Miltich, all of North Carolina State University in Raleigh.

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center manages the Chandra program. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory’s Chandra X-ray Center controls science from Cambridge Massachusetts and flight operations from Burlington, Massachusetts.

Chandra :: Photo Album :: MSH 15-52 :: June 24, 2021 (si.edu)

EXPLAINING THE HIDDEN MEANING OF MICHELANGELO’S CREATION OF ADAM

EXPLAINING THE HIDDEN MEANING OF MICHELANGELO’S CREATION OF ADAM

FRANK LYNN MESHBERGER, MD AND TONY B. RICH

FAN INTERPRETATION OF MICHELANGELO’S CREATION OF ADAM BASED ON NEUROANATOMY AND THE USE OF SYMBOL AS A METAPHOR OF MEANING

The Creation of Adam (1508-1512) on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel has long been recognized as one of the world’s great art treasures. In 1990 Frank Lynn Meshberger, M.D. described what millions had overlooked for centuries — an anatomically accurate image of the human brain was portrayed behind God. On close examination, borders in the painting correlate with sulci in the inner and outer surface of the brain, the brain stem, the basilar artery, the pituitary gland and the optic chiasm. God’s hand does not touch Adam, yet Adam is already alive as if the spark of life is being transmitted across a synaptic cleft. Below the right arm of God is a sad angel in an area of the brain that is sometimes activated on PET scans when someone experiences a sad thought. God is superimposed over the limbic system, the emotional center of the brain and possibly the anatomical counterpart of the human soul. God’s right arm extends to the prefrontal cortex, the most creative and most uniquely human region of the brain.

The brilliant Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo Buonarroti painted magnificent frescoes on the ceiling of the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel, laboring from 1508 to 1512. Commissioned by Pope Julius II, Michelangelo performed this work himself without assistance. Scholars debate whether he had any guidance from the Church in the selection of the scenes, and what meaning the scenes were to convey. In the fresco traditionally called the Creation of Adam, but which might be more aptly titled the Endowment of Adam, I believe that Michelangelo encoded a special message. It is a message consistent with thoughts he expressed in his sonnets. Supreme in sculpture and painting, he understood that his skill was in his brain and not in his hands. He believed that the “divine part” we “receive” from God is the “intellect”. In the following sonnet, Michelangelo explains how he creates sculpture and painting and how, I believe, God himself gave man the gift of intellect (1) :

After the divine part has well conceived

Man’s face and gesture, soon both mind and hand,

With a cheap model, first, at their command,

Give life to stone, but this is not achieved

By skill. In painting, too, this is perceived:

Only after the intellect has planned

The best and highest, can the ready hand

Take up the brush and try all things received.

The sculpture and painting of Michelangelo reflect the great knowledge of anatomy that he acquired by performing dissections of the human body. His experience in dissection is documented in Lives of the Artists, written by his contemporary, Georgio Vasari (2).

Vasari says, “For the church of Santo Spirito in Florence Michelangelo made a crucifix of wood which was placed above the lunette of the high altar, where it still is. He made this to please the prior, who placed rooms at his disposal where Michelangelo very often used to flay dead bodies in order to discover the secrets of anatomy . . .”

The Creation of Adam fresco shows Adam and God reaching toward one another, arms outstretched, fingers almost touching. One can imagine the spark of life jumping from God to Adam across that synapse between their fingertips. However, Adam is already alive, his eyes are open, and he is completely formed; but it is the intent of the picture that Adam is to “receive” something from God. I believe there is a third “main character” in the fresco that has not previously been recognized. I would like to show this by looking at four tracings, Figures 1 through 4, and by reviewing gross neuroanatomy, using works by Frank Netter, MD, illustrator of The CIBA Collection of Medical Illustrations, Volume I — The Nervous System.

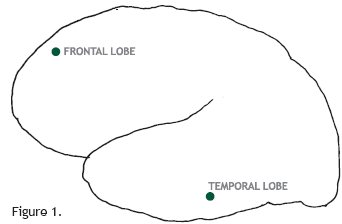

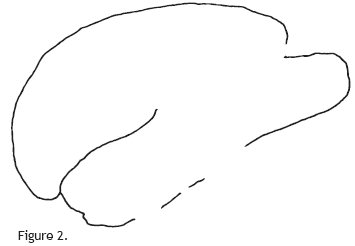

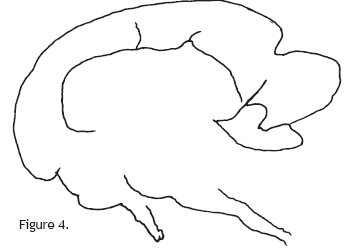

Examine Figures 1 and 2 to see if there is any similarity between them. Examine Figures 3 and 4 and decide if these figures are similar or dissimilar. Take enough time inspecting the figures so that your mind may form its own image of them.

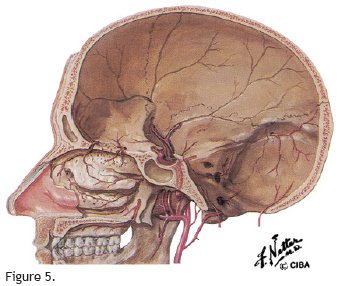

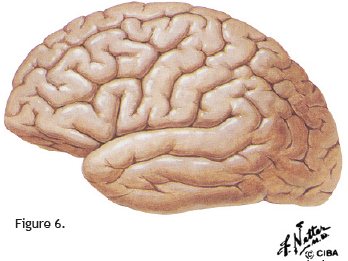

Proceeding to the neuroanatomy, Figure 5 shows a saggital section of the skull; the brain, which lies in the cranium, takes its shape from it. Study the picture to gain an overall impression of the shape of the cranium. Figure 6 shows the left lateral aspect of the brain and illustrates the sulci and gyri that are present in the hemispheres. The fissure of Silvius, or lateral cerebral fissure, separates the frontal lobe from the temporal lobe. Figure 1 is a tracing of this illustration.

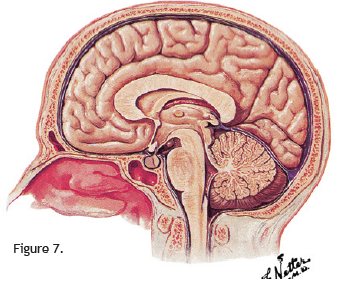

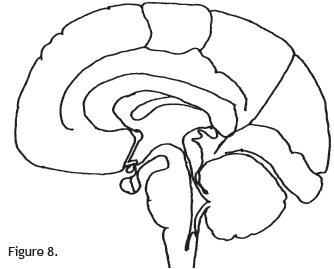

Figure 7 depicts the medial aspect of the right hemisphere; Figure 8 is a tracing of the brain and spinal cord portion of this illustration. The sulcus cinguli separates the gyrus cinguli from the superior frontal gyrus and paracentral gyrus. The parietal lobe is divided into the cuneus and lingular gyrus. The pituitary gland is seen lying in the pituitary fossa; the fact that the pituitary is bilobed can be seen grossly. The pons, the bulbous upward extension of the spinal cord, is noted. Immediately in front of the pituitary gland is the cross section of the optic chiasm. Figure 3 is derived from Figure 8 by removing both the cerebellum and the midbrain structures inferior to the gyrus cinguli and rotating the spinal cord posteriorly from the standard anatomic position.

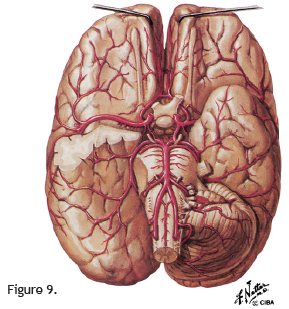

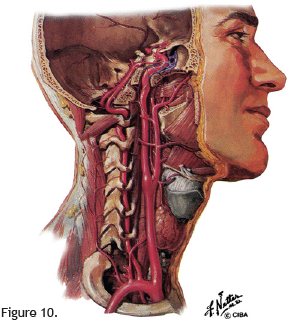

Figure 9 is the inferior surface of the brain. From the optic chiasm, the optic nerves extend rostrally, and the optic tracts pass backward across the cerebral pedicles. The basilar artery, formed by the junction of the two vertebral arteries, extends from the inferior to the superior border of the pons. Figure 10 shows the vertebral artery running cranial-ward through the foramen in the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae to the inferior surface of the skull. The vertebral artery bends abruptly around the articular process of the atlas and makes another abrupt bend to enter the cranial cavity through the foramen magnum, where it joins the other vertebral artery to form the basilar artery.

Having studied these images of neuroanatomy, proceed to Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam (Figure 11) and look at the image that surrounds God and the angels.

This image has the shape of a brain.

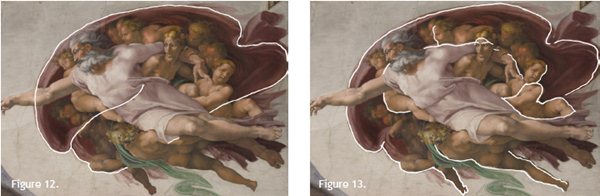

Figure 12 shows that Figure 2 is obtained by tracing the outer shell and the sulcus. Figure 13 shows that Figure 4 is a tracing of the outer shell and of major lines in the fresco of God and the angels. Therefore, Figures 1 and 3 are tracings of neuroanatomy drawn by Frank Netter, and Figures 2 and 4 are tracings from the Creation of Adam by Michelangelo.

The sulcus cinguli extends along the hip of the angel in front of God, across God’s shoulders, and down God’s left arm, extending over Eve’s forehead. The flowing green robe at the base represents the vertebral artery in its upward course as it twists and turns around the articular process and then makes contact with and proceeds along the inferior surface of the pons. The back of the angel extending laterally below God represents the pons, and the angel’s hip and leg represent the spinal cord. The pituitary stalk and gland are depicted by the leg and foot of the angel that extends below the base of the picture. Note that the feet of both God and Adam have five toes; however, the angel’s leg that represents the pituitary stalk and gland has a bifid foot. This same angel’s right leg is flexed at the hip and knee; the thigh represents the optic nerve, the knee the transected optic chiasm, and the leg the optic tract.

The important point, however, is not to identify minute neuroanatomic structures in the fresco, but to see that the larger image encompassing God is compatible with a brain. Michelangelo portrays that what God is giving to Adam is the intellect, and thus man is able to “plan the best and highest” and to “try all things received”.

References :

1. Tusianai J. The Complete Poems of Michelangelo. New York, NY: Noonday Press; 1960:146-147.

2. Vasari G; Bull G, trans. Lives of the Artists. Middlesex, England: Penguin Classics; 1965:332-333.

The above article appeared in the October 10, 1990 edition of JAMA®, The Journal of the American Medical Association, Volume 264, No. 14.