Follow the Money & Power Holders

What can account for this phenomenon?

Click Here

On average, successful municipal campaigns in Ottawa received 46% of their contributions from individuals with ties to the development industry. In reality, eleven members of council received a majority of their campaign contributions from

After this report and then the recent Cullen Commission on Money Laundering with a hundred one (101) Recommendations since May 2022. What's next?

Follow the Money & Power Holder

Developer Donations and Campaign Finance Reform in the City of Ottawa

May 2020

Follow the Money

Developer Donations and Campaign Finance Reform in the City of Ottawa

Executive Summary

Nearly a million dollars ($939,573) was donated to the successful candidates in Ottawa’s 2078 municipal election. The twenty-three councillors, elected to represent us, collectively received $557,725 in campaign donations and our returning Mayor raised a total of $388,388 for his reelection campaign. This investment in the political future of

twenty-four politicians was not the result of political party contributions, public funding, or simple self-financing, but the private donations of motivated donors.

As residents of Ottawa, we would like to imagine that our local democracy is fueled by small donations made by our civically engaged neighbours. These small donations should be an important part of a healthy municipal democracy, allowing for individuals to support candidates they believe in and for popular candidates to get their message out there.

However, campaign financing in Ottawa is much more complicated.

Nearly half of the total campaign contributions donated candidates elected in the 2078 municipal election ($432,777) came from donors who had personal or professional ties to firms with financial interests in the planning, building, or selling of properties and buildings, in other words, from the development industry. Thenumber grows even higher when we include candidates who were not successful in being elected to $527,287. No other industry appears to be this invested in financing municipal elections, nor in helping to elect local representatives who go on to regulate planning and development in the city.

By combining publicly available financial statements listed on the City of Ottawa’s website, and research on the employment and public profiles of donors, this report classifies nearly every disclosed donation made to a successful municipal campaign in the 2078 election and the 2079 by-election. These financial statements are required by the Municipal Elections Act, 7996 to be completed and published to ensure political transparency.

The extent to which campaign contributors with developer connections are financing municipal election campaigns is deeply troubling. For example, twenty-seven executives of the Taggart Property Development company and their families contributed a combined

$32,400 to the mayoral election of Jim Watson, each one of them contributing the maximum amount ($7,200.00). This single company represents 8.3% of all donations contributed to the Mayor’s campaign. The Chair of the Planning Committee received

$39,724 in campaign contributions from only fifty residents – forty-two of whom have ties to the development industry and who represent 96% of her donations.

Executive Summary

On average, successful municipal campaigns in Ottawa received 46% of their contributions from individuals with ties to the development industry. In reality, eleven members of council received a majority of their campaign contributions from

developer-connected donors, with four councillors receiving 80% or more of their funding from these donors. It should be noted that it is entirely within a councillor’s legal rights to solicit these donations and for executives of property development companies to contribute. Thequestions we must grapple with, however, are: why are individuals employed by, or associated with, the development industry so overrepresented among election donations?

Why does no other industry or group take such an avid interest in funding municipal campaigns? And, what does this mean for municipal democracy in Ottawa?

At the provincial level, there have been some positive steps taken toward reforming municipal election-financing rules. For instance, the recent ban on corporate and union donations. However, the following research shows that this policy has had limited impact on stemming the tide of donations still connected to corporate interests. Senior executives, along with their spouses and relatives, continue to donate thousands of dollars through individual donations to municipal candidates.

The authors of this report undertook this public interest research because they feel that the development industry has too much influence at City Hall. Property developers are too often prioritized above citizens as the principal stakeholders in the planning processes in the City of Ottawa. The city makes land-use decisions and infrastructure investments which profoundly affect our lives as residents, but these decisions also shift the value of property as an investment, and thus the financial positions of interested parties. There should be no ambiguity in ensuring the public interest takes priority over private gain in all planning decisions.

This report does not constitute a blanket discrediting of development. Ottawa needs to develop as the city continues to grow. However, development should be done in a way that prioritizes making Ottawa livable, affordable, and sustainable for all its residents. In short, development must be in the public interest. In order for this to occur, municipal politicians must be better insulated from the financial power of the development industry. We argue that this requires reforming our municipal campaign finance system. Ultimately, it is our hope that this report and its accompanying data sets will allow readers to have further insight into the world of municipal politics so they can draw their own conclusions.

Key Findings

A Comprehensive Report on Developer Donations and Campaign Finance Reform in the City of Ottawa

Key Findings… 1

Methodology 6

Discussion… 8

Conclusion… 12

Overview of Findings… 13

References… 19

Key Findings

The financial statements from the most recent municipal elections in Ottawa clearly show that contributions from individuals associated with the development industry make up a significant portion of total campaign contributions. Of the 24 members of City Council elected in 2078 and 2079, 77 were funded primarily by contributions from those connected to the development industry. 4 more councillors received between 75-49% of their funds from the development industry and a further 3 received a small amount of developer donations.

Only 6 of 24 members of City Council were elected without taking donations from individuals with links to the development industry.

There is an apparent geographic divide in the distribution of donations as all 6 councillors who abstained from developer donations represent downtown wards. These donations also seems to favour incumbent councillors. Of those who took 50% or more, only

Gloucester-South Nepean Councillor, Carol Anne Meehan was not the incumbent. Mayor Jim

Watson outraised his 77 opponents by 3 times just through contributions from the development industry alone, totaling $203,367 from the industry. We also noticed that councillors who did not receive developer donations tend to lack a presence on key leadership and planning committees at City Hall.

The Finance and Economic Development Committee (FEDCO)

The most important City Council Committee, the Finance and Economic Development Committee (FEDCO), is colloquially known at City Hall as the ‘Mayor’s cabinet’ or ‘executive committee’. The Committee is made up of all the Chairs of the other city committees, the deputy Mayors, and is chaired by the Mayor. FEDCO is also made up exclusively of Councillors who received donations from the development industry and over represents members of council whose campaigns were funded primarily through developer donations (46% of all members of city council versus 58% of the members of FEDCO). Both sitting councillors who received over 90% of their contributions from developer donations are present in this committee. Those who did not receive these donations have been virtually shut out of representation of positions of leadership at City Hall, leaving these voices woefully

underrepresented. 1

The Planning Committee & The Agriculture and Rural Affairs Committee

The Planning Committee and the Agriculture and Rural Affairs Committee (ARAC) are also powerful committees at City Hall, and are particularly relevant to the issue of development industry influence in Ottawa. According to the City of Ottawa’s website, the Planning Committee is meant to “review and make decisions on the merits of development applications and policy with an urban focus,” while ARAC serves a similar function for rural areas. That ARAC is populated by Councillors who represent, and thus have a stake in the decisions that affect, those wards, is logical, but this same logic is not observed for the Planning Committee. The Planning Committee has only one urban member (Jeff Leiper).

Meanwhile, there are two members from rural areas who serve on both committees (Scott Moffatt and Glen Gower), and up until the end of February of 2020, there was a third rural member on the Planning Committee: Councillor Blais – who resigned after successfully running to be a Member of Provincial Parliament.

Members of these committees relied heavily on development industry contributions to fund their 2078 elections. On the Planning Committee, 58% of funds raised were contributed by individuals associated with the development industry, with 5 of 9 members being funded more than 50% by these contributions, for an average of $73,878 per member. ARAC is similarly funded, with 4 of 5 members raising more than half of their election funds in this manner. Members of ARAC combined took 57% of their election contributions from the development industry, with an average of $72,050 per member. Please note that the figures have decreased as of February 2020 with the departure of Councillor Blais who received 90% of funds raised from individuals associated with the development industry.

Jan Harder was appointed to continue as Chair of the Planning Committee after 95% of her re-election campaign contributions (over $37,000) came from the development industry. Eli EI-Chantiry was appointed Chair of ARAC after taking over 70% of his re-election campaign contributions ($76,850) from the development industry. Allan Hubley, a fellow Council Committee Chair (Transit Commission) and FEDCO member, is also a member of the Planning Committee. Hubley took the most developer contributions, as a percentage of

2

Developer Connected Contributions

$26,200.00

Tim Tierney- Member

$26,400.00

Allan Hubley – Member

Developer Connected Contributions

$37,250.00

Jan Harder – Chair

Developer Connected Donations to Planning Committee, 2018

>>>

Developer Connected Contributions

$0.00

Jeff Leiper – Member

Developer Connected Contributions

$250.00

Glen Gower-Vice Chair

Developer Connected Contributions

$3,200.00

Laura Dudas – Member

Developer Connected Contributions

$3,250.00

Riley Brockington – Member

Developer Connected Contributions

$11,350.00

Scott Moffatt – Member

Developer Connected Contributions

$17,000.00

Rick Chiarelli – Member

3

Key Findings

total contributions, of any other Council member with 99% of his total campaign contributions ($26,400) coming from individuals associated with the development industry.

As per the City’s governance rules, each committee also includes the Mayor as an ex officio member. Mayor Jim Watson received over $200,000 (53%) from the development industry. As well, Planning Chair Jan Harder has the privilege as an ex officio member of ARAC, while her counterpart Eli EI-Chantiry holds the same privilege at Planning Committee.

Needless to say, development industry-connected contributions in 2078 municipal election campaigns correspond closely with representation on the 2 committees that impact the industry most. These Committees ensure that development applications, site plan applications, zoning amendments, and Official Plan amendments are approved, securing large and small developments in all areas of the city.

Although there are regulations that have been put into place to ban corporate contributions in municipal elections, the data would suggest that the development industry has found creative ways around this. The most egregious example is the Taggart Group of Companies. The individuals and families connected to Taggart donated a total of $71,950, with close to half ($32,400) donated to Mayor Jim Watson’s campaign. The data also shows that the vast majority of councillors on FEDCO (9 out of 11), took money from contributors connected to Taggart.

Other ways council candidates may skirt the spirit, if not the letter, of electoral financing law is through attending privately hosted fundraisers. As CBC reporter, Joanne Chianello, reported in 2078, Councillors Jan Harder, Jean Cloutier and Stephen Blais all attended, or planned to attend fundraisers hosted specifically for members of the development industry to rub shoulders with the decision-makers that most impact their financial interests (Cloutier’s fundraiser ended up being cancelled as a result of public scrutiny). In Harder’s case, an email was sent out to about 30 industry executives to make a cheque for the amount of $7,200 (the maximum campaign contribution) in order to attend a fundraiser organized by Jack Stirling, Minto’s former VP of development.

4

Methodology

This research project began in April 2079, soon after the Financial Statements were released by Councillors following the 2078 Municipal elections which are readily available for public access on the City of Ottawa website. These statements- sworn to be accurate by each candidate who stood for election -discloses names, home addresses, and the date contributions were made, for all campaign contributors who donated $700 or more. Each individual is legally bound to contribute no more than $7,200 to any municipal election candidate, and no more than $5,000 in their name for each municipal election in Ontario.

The figures in this report represent contributions found to be made by individuals who are, or are related to, either executives, owners, or representatives of real estate development, property management, or core infrastructure industries, as well as individuals who are, or are related to, contractors, consultants, legal or financial service providers that do business with the commercial and residential construction industry. These contributors are found in lists provided in Schedule l of the Financial Statement for each candidate in the 2078 Ottawa Municipal election, as well as the 2079 By-election in Rideau-Rockcliffe Ward. This definition is used throughout the report as the basis for any mention of developer donations or development industry contributions.

Each contributor was researched thoroughly in an attempt to determine whether they represented a development industry interest using the searchable database available at ottwatch.ca to cross-reference with the statements published on the City of Ottawa website. This research was supplemented with external information found in publicly available online resources: company websites, databases such as the Tarion Builder Registry’s website, newspaper articles, and social media platforms such as LinkedIn.

Further, address information disclosed for each contributor was compared in order to determine familial connections between donors and stakeholders within the development industry. These connections were further established using online publications such as news articles, published obituaries or photo spreads from the local circuit of charity galas.

6

Methodology

A pattern wasfound of contributions being submitted under multiple names within the same household or family, which add up to more than the individual donation limit of $5,000. That said, many of those who did break the law by donating more than $5,000, were not held responsible by the City. In one example, noted by Ottawa Citizen journalist Jon Willing in December 2079, the citizen body responsible for prosecuting breaches of the Municipal Elections Act, the Elections Compliance Audit Committee (ECAC), decided not to pursue the prosecution of five development industry donors for over-contributing as they did not believe it was in the public interest. The developers in question blamed the illegal donations on having lost count of how much they or their spouse had donated, or on accidentally writing a cheque from the wrong bank account.

The database compares the sums of development industry connected contributions aggregated for each candidate to the total funds raised by that candidate to determine the percentage of total contributions that stem from the development industry. All sums claimed to be contributed by the candidate or their spouse have been omitted from fundraising totals, as well as any costs that account for campaign supplies that were carried forward from a previous municipal campaign. These totals are also listed in Schedule l of the Financial Statement. They represent costs or sums that arenot subject to the individual contribution limits or disclosure rules.

The purpose of this database, and the analysis thereof, is to provide residents with a tool to better understand the role the development industry plays in financing election campaigns of municipal politicians in Ottawa. It attempts to capture, as comprehensively and accurately as possible, all those campaign contributors who have a financial stake in the decisions made regarding the built environment of the City of Ottawa. However, there are limits to what can be accurately determined or implied. In many cases, it was not possible to make a strong connection between a contributor and a development industry interest that they may have a stake in. For this reason, the list is surely incomplete and omits some additional contributors to municipal campaigns who could fit the defined criteria. It is expected that the database will continue to grow and be refined as more information is found or made available.

7

Discussion

In the Spring of 2076, the Ontario Liberal government adopted Bill 68 in an effort to lessen the development industry’s influence in municipal politics, both real and perceived. The Bill banned corporate and union donations, and allowed for “third-party advertisers,” meaning that businesses and other organizations wishing to release ads related to the municipal election would have to register the same way candidates do and be subject to their own financing rules. Upon closer examination, however, the Bill had its faults: not only does the Bill permit corporations to be third-party advertisers, but it also raised the individual contribution limit by 60% from $750 to $7200 (Chianello, 2076).

Developers continue to play a large role in municipal politics in Ontario and beyond as a result of inadequate election financing laws that pave the way for a planning process that prioritizes development industry profits over community input and plans. A more

pro-developer council makes it increasingly difficult for the public to succeed in pushing for their priorities, which tend to be at odds with cheap sprawling development, and guaranteeing profits for the development industry.

The perception of the disproportionate influence that developers have over elected municipal officials is a well-studied phenomenon by scholars of municipal politics. In fact, some theorists, such as Professor Anna Domaradzka from the University of Warsaw’s Institute for Social Studies, have gone so far as to charachterize urban governance as a negotiated conflict between ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’ both “seeking control over urban space and investment priorities” (2077). The outcome, Domaradzka says, is the “result of interplay between local governments and developers (as incumbents) in which urban activists are serving the role of challengers.”

This interplay extends beyond elections and into the everyday workings of the city in the form of two relationships between City Council and the development industry. First, municipalities rely on developers to be the prime movers of urban development (Domaradzka, 2077). Urban growth is ‘developer-led’, and while it is governmentally

8

Discussion

managed through “growth management plans, land use zoning, and (formal and informal) negotiations,” ultimately municipal governments “cannot compel developers to build” (Leffers, 2078). Second, development is crucial to city budgets as developers pay development charges, new residents pay property taxes, and attendant rising property values further augment revenue from the latter.

While municipalities and developers necessarily work together to drive urban development, tensions can arise when municipalities’ plans for their cities contradict developer’s desire for profits. For example, city government is responsible for regulating developers to make sure they follow local zoning bylaws. When these bylaws are not desirable, developers will often pursue amendments and variances. Most often these are granted, but in some instances this is not the case. This creates a challenge for developers who at times have stakes in the millions of dollars in certain development projects. As a result of this inevitable conflict, both parties can come to believe that they need each other for continued political and financial survival (Leffers, 2078).

Developers are acutely aware that good relationships with City Councillors are central to the work of development. For example, in a series of interviews conducted with developers, Leffers (2078) found that developers thought their relationships with municipal governments were generally of “central importance.” Brown University Professor of Sociology, John R Logan, has gone so far as calling this system the “Growth Machine,” wherein organized real estate professionals contribute to municipal campaigns and deepen their partnerships with municipal leaders to steer development activity in their favour (2007).

There are obvious issues with the second part of this relationship, mostly the way in which it presents itself to the general public and the perception it leaves. Robert MacDermid, Professor Emeritus at York University, has studied this issue extensively. While MacDermid’s case studies largely focus on the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), it is reasonable to assume that the dynamics he identifies there also exist in Ottawa. MacDermid (2009) found that in numerous past municipal elections in the GTA candidates were funded mainly by the development industry.

9

Discussion

Across all of the elections he reviewed, the development industry contributed between half to nearly two-thirds of all corporate contributions (MacDermid, 2007). This situation is unique: at no other level of government does a single industry dominate elections financing to such a large degree (MacDermid, 2009). Furthermore, MacDermid found that “development industry funding is far greater where the value of building permits is the highest and where more developers have projects in the approval process that are dependent on council decisions” (Noor, 2076). In other words, when the financial stakes for developers are higher, developer spending on election campaigns also increases.

In Canada and around the world, there have been many efforts by different municipal governments to try and mitigate the perceived influence of corporate money in local politics. Many of these jurisdictions provide tools that both the City of Ottawa and province of Ontario can learn from. New York City for example provides a strong example of improving public financing of election campaigns through their “matching funds” program. It consists of matching small campaign funds at a 6:7 ratio, once they pass certain fundraising thresholds (Brennan Centre for Justice, 2079). As Executive Director of Washington’s Campaign Finance Institute, Michael J. Malbin explains, this strategy encourages candidates to seek donations from individuals who are not normally considered to be part of the ‘donor class’ (2079).

Other public financing systems that exist 1n some American municipalities, like lump-sum grant programs, mitigate developer influence as donors all donate to a central campaign fund (Demos, 2077). Multiple studies from New York’s Brennan Centre for Justice have shown that models of public financing not only increase the number of low-income contributors in general, but also the diversity of those who donate. Public financing was also shown to decrease the margin of victory in, and increase the competitiveness of, elections (Brennan Centre, 2079). Other methods of reform also include policies such as lowering the contribution limit. Like public financing, Thomas Stratman, an economist at George Mason University, has shown that, in many cases, lowering the limit tends to widen the field of candidates and make elections more accessible and competitive (2005).

10

It is clear that the relationship between our local elected officials and the development industry is one that is influential not only during elections but also in the minutiae of

day-to-day life in our city. It is important to ask, however, where residents fit in the middle of this ‘negotiated relationship’ between developers and city officials, and how their interests can be put forward on a more level playing field. As other municipalities have shown, this can be achieved, but reforms — more ambitious than those proposed by the Liberals in 2076 — are needed.

11

Conclusion

This report has attempted to delve into the reasons and motivations behind the industry with regards to the funding of political candidates and campaigns. Some may argue that a donation is simply that – a donation: a simple financial exchange to show support for their community, or their vision for their community, and every resident can donate accordingly within existing limits. This argument, however, presents a pretense that every resident has similar access to resources to express their interests, and those interests are thus equally pursued. This assumption has allowed many councillors and candidates to escape and eschew public scrutiny. The source of a candidate’s contributions can, in fact, tell us a lot about what and who they stand for, as one source of contributions can contribute significantly to their electoral success.

Reforms are needed, but will not alone remove the influence of developers at City Hall.

Developer influence manifests in many other areas as well, namely due to the massive role private development continues to play in shaping our built environment, and the various ways public planning has become structured around that fact. If residents wish to regain power and control over their communities and neighbourhoods they must organize themselves around City-wide principles of improving transparency and democracy, making the City more livable and ecologically friendly, and enhancing policies around accessibility and inclusion.

12

https://documents.ottawa.ca/sites/documents/files/compliancereport_candidates_en.pdf

19

MacDermid, Robert. (June 2007). Campaign Finance and Campaign Success in Municipal Elections in the Toronto Region. Paper Presented at the Annual General Meetings of the Canadian Political Science Association. Retrieved from:

https://www.cpsa-acsp.ca/papers-2007/MacDermid.pdf.

MacDermid, Robert. (2009). Funding city politics; municipal campaign funding and property development in the greater Toronto area. Vote Toronto. Scholars Portal Books.

Mai bin M. et al. (2079, February). Small-Donor Matching Funds for New York State Elections: A Policy Analysis of the Potential Impact and Cost. Campaign Finance Institute. Retrieved from: http://www.cfinst.org/pdf/State/NY/Policy-Analysis_Public-Financing-in-NY-State_Feb2079_w Appendix.pdf.

Stratman et al. (2005, July 22). Competition policy for elections: Do campaign contributions matter? Public Choice. Retrieved from:

Theory of Regulatory Capture. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 706 (4). ProQuest.

Willing J. (2079, December 6). Committee votes against prosecuting developers after election spending reviews. Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved from

https://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/committee-votes-against-prosecuting-developer s-after-election-spending-reviews

20

INVESTIGATION REPORTS

The Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner investigates and reports publicly on alleged contraventions of the Conflict of Interest Act and the Conflict of Interest Code for Members of the House of Commons.

Investigations under the Act are called “examinations” and investigations under the Code are called “inquiries“. In some cases, an individual may be investigated under both regimes.

At the conclusion of an investigation, the Commissioner issues a report.

EXAMINATION REPORTS UNDER THE ACT

Scott Report – August 24, 2022

Morneau II Report – May 13, 2021

Trudeau III Report – May 13, 2021

Report on alleged wrongdoing by a Deputy Minister – September 30, 2020

Report on alleged wrongdoing by a tribunal member – July 9, 2020

Qualtrough Report – April 22, 2020

Miller Report – April 22, 2020

Wernick Report – March 10, 2020

Trudeau II Report – August 14, 2019

Smolik Report – May 30, 2019

Kristmanson Report – December 12, 2018

LeBlanc Report – September 12, 2018

Chapman Report – June 22, 2018

Morneau Report – June 18, 2018

Carson Report – June 7, 2018

The Trudeau Report, under the Act and the Code – December 20, 2017

The Wright Report – May 25, 2017

The Toews Report – April 21, 2017

The Philpott Report – December 21, 2016

Referral from the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner: The Bennett Report – November 17, 2016

The Vennard Report – September 13, 2016

The Gill Report – February 24, 2016

The Kosick Report – September 15, 2015

The Finley Report – March 10, 2015

Referral from the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner: The Bonner Report – February 26, 2015

Referral from the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner: December 2014 Report – December 4, 2014

The Glover Report – November 20, 2014

The Lynn Report – June 26, 2014

The Paradis Report, under the Act and the Code – December 3, 2013

The Paradis Report – August 7, 2013

Referral from the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner: The Fonberg Report – April 30, 2013

The Hill Report – March 26, 2013

The Sullivan Report – October 17, 2012

Referral from the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner: The Clement Report – July 18, 2012

Referrals from the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner: The Heinke and Charbonneau Report – May 18, 2012

The Raitt Report – April 26, 2012

The Paradis Report – March 22, 2012

The Dykstra Report, under the Act and the Code – September 7, 2010

The Raitt Report – May 13, 2010

The Cheques Report – April 29, 2010

Discontinuance Report relating to an examination of allegations of partisan advertising of government initiatives – January 13, 2010

The Watson Report – June 25, 2009

The Flaherty Report – December 18, 2008

The Flaherty Report – July 16, 2008

The Soudas Examination – June 4, 2008

INQUIRY REPORTS UNDER THE CODE

Ratansi Report – June 15, 2021

Maloney Report – November 19, 2020

Peschisolido Report – February 5, 2020

Vandenbeld Report – July 10, 2019

Kusie Report – December 4, 2018

Angus Report I – June 14, 2018

Angus Report II – June 14, 2018

The Trudeau Report, under the Act and the Code – December 20, 2017

The Paradis Report, under the Act and the Code – December 3, 2013

The Guergis Report – July 14, 2011

The Dykstra Report, under the Act and the Code – September 7, 2010

The Raitt Report – May 13, 2010

The Cheques Report – April 29, 2010

Response to the motion adopted by the House of Commons on June 5, 2008 for further consideration of The Thibault Inquiry Report – June 17, 2008

The Thibault Inquiry – May 7, 2008

The following inquiry reports under the Code, which was adopted by the House of Commons in April 2004, were issued by the Office of the Ethics Commissioner, a predecessor of the Office of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner.

The Obhrai Inquiry – March 2007

The Vellacott Inquiry – June 2006

The Gallant Inquiry – June 2006

The Harper-Emerson Inquiry – March 2006

The Grewal-Dosanjh Inquiry – January 2006

The Smith Inquiry – December 2005

The Grewal Inquiry – June 2005

THE TRUDEAU REPORT I, II, III

Trudeau I Report

Under the Act and the Code – December 20, 2017

The Trudeau Report.pdf (parl.gc.ca)

Trudeau II Report

August 14, 2019

Trudeau III Report (parl.gc.ca)

May 2021

Investigation Reports (parl.gc.ca)

≡ Relative Knowledge ≡

Home » Follow the Money & Power Holder

On What Matters

Bookmarkable

The Commission is committed to continuing with its important work for the

Psephology and the 45th Canadian Federal Election 2025: A Fun Guide |

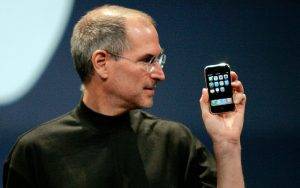

Guiding Words in Steve Jobs’ Mind Leading to the Advent of the

Table of Contents The outsourcing challenge Organizing workers across fragmented production networks

達芙妮·布拉姆漢姆:溫哥華市長利用開發商為連任提供資金|溫哥華太陽報

Pierre Poilievre has the charisma of not being charismatic What can account

What can account for this phenomenon? Click Here Table of Contents Bank