| This Act is current to June 16, 2021 |

| See the Tables of Legislative Changes for this Act’s legislative history, including any changes not in force. |

[RSBC 1996] CHAPTER 57

Payment by execution creditor of rent before removal of chattels taken in execution

1 No chattels being in or on any land that is or shall be leased for life or lives, term of years, or at will, or otherwise, are liable to be taken by virtue of any execution, unless the party at whose suit the said execution is sued out, before the removal of such chattels from the premises, by virtue of such execution or extent, pays to the landlord of the premises or the landlord’s bailiff such sum of money as is due for rent for the premises at the time of the taking of the chattels by virtue of the execution, if the arrears of rent do not amount to more than one year’s rent; and in case the said arrears exceed one year’s rent, then the party at whose suit such execution is sued out, paying the said landlord or bailiff one year’s rent, may proceed to execute his or her judgment, as he or she might have done heretofore; and the sheriff or other officer is empowered and required to levy and pay to the plaintiff as well the money so paid for rent as the execution money.

Action against tenant for life for rent

2 Any person having any rent in arrear or due on any lease or demise for life or lives may recover such arrears of rent by action as if such rent were due and reserved on a lease for years.

Rent in arrear on a lease expired may be distrained for after determination of lease

3 Any person having any rent in arrear or due on any lease for life or lives, or for years, or at will, ended or determined, may distrain for such arrears, after the determination of the said respective leases, in the same manner as he or she might have done if such lease or leases had not been ended or determined.

Provided distress be made within 6 months after determination of lease

4 Distress under section 3 shall be made within the space of 6 calendar months after the determination of the lease, and during the continuance of the landlord’s title or interest, and during the possession of the tenant from whom the arrears became due.

Provision for landlords where tenants desert premises

5 And whereas landlords are often sufferers by tenants running away in arrear, and not only suffering the demised premises to lie uncultivated without any distress thereon, whereby their landlords might be satisfied for the rent-arrear, but also refusing to deliver up the possession of the demised premises, whereby the landlords are put to the expense and delay of recovering in ejectment: Be it enacted —

That if any tenant holding any land at a rack-rent, or where the rent reserved is full three-fourths of the yearly value of the demised premises, who is in arrear for one year’s rent, deserts the demised premises and leaves the same uncultivated or unoccupied, so as no sufficient distress can be had to countervail the arrears of rent, it is lawful for 2 or more Justices of the Peace of the county, district or place, at the request of the landlord or the landlord’s bailiff or agent, to go on and view the same, and to affix, or cause to be affixed on the most conspicuous part of the premises notice in writing what day (not less than 14 days thereafter) they will return to take a second view thereof; and if on such second view the tenant, or some person on the tenant’s behalf, does not appear, and pay the rent in arrear, or there is not sufficient distress on the premises, then the said justices may put the landlord into the possession of the said demised premises, and the lease thereof to such tenant, as to any demise therein contained only, shall from thenceforth become void.

Tenants may appeal from justices

6 Proceedings under section 5 are subject to review in a summary way by any judge of the Supreme Court, who may order restitution to be made to the tenant together with his or her expenses and costs, to be paid by the landlord, or to make such order as the judge shall think fit; and in case the judge affirms the act of the justices, the judge may award such costs of appeal in favour of the landlord as may seem just.

Method of recovering rentseck

7 Every person shall and may have the like remedy by distress and by impounding and selling the same, in cases of rentseck, rents of assize, and chief rents, as in case of rents reserved on lease, any law or usage to the contrary notwithstanding.

Chief leases may be renewed without surrendering all underleases

8 (1) In case any lease is duly surrendered in order to be renewed, and a new lease made and executed by the chief landlord, the same new lease is, without a surrender of any of the underleases, as valid as if all the underleases derived from it had been likewise surrendered at or before the taking of such new lease.

(2) Every person in whom any estate for life or lives, or for years, is from time to time vested by virtue of the new lease, and his or her personal representatives, are entitled to the rents, covenants and duties, and shall have like remedy for recovery thereof, and underlessees shall hold and enjoy the land in the respective underleases comprised as if the original leases out of which the respective underleases are derived had been still kept on foot and continued.

(3) The chief landlord shall have and is entitled to such and the same remedy, by distress or entry in and on the land comprised in the underlease, for the rents and duties reserved by the new lease, so far as the same exceed not the rents and duties reserved in the lease out of which such underlease was derived, as the chief landlord would have had in case the former lease had been still continued, or as the chief landlord would have had in case the respective underlease had been renewed under the new principal lease.

Rents, how to be recovered where demises are not by deed

9 (1) It is lawful for the landlord, where the agreement is not by deed, to recover by action in any court of competent jurisdiction a reasonable satisfaction for the land held, used or occupied by the defendant for the use and occupation thereof.

(2) If at the trial of the action it appears that any rent has been reserved by a parol, demise, or any agreement (not being by deed), such rent may be the measure of the damages to be recovered by the plaintiff.

Rents recoverable from undertenant where tenants for life die before rent is payable

10 Where any tenant for life dies before or on the day on which any rent was reserved or made payable on any demise or lease of any land which determined on the death of the tenant for life, the personal representatives of the tenant for life shall and may recover from any undertenant or undertenants of the land if the tenant for life dies on the day on which the same was made payable, the whole, or if before such day then a proportion, of the rent according to the time the tenant for life lived, of the last year or quarter of a year, or other time in which the rent was growing due as aforesaid, making all just allowances or a proportionable part thereof respectively.

Certain other rents to be considered as within provisions of section 10

11 Rents reserved and made payable on any demise or lease of land determinable on the death of the person making the same (although such person was not strictly tenant for life thereof) or on the death of the life or lives for which the person was entitled to the land, shall, so far as respects the rents reserved by the lease, and the recovery of a proportion thereof by the person granting the same, his or her personal representatives, be considered as within the provisions of section 10.

Apportionment and recovery of rents, annuities, and payments due at fixed periods

12 All rents-service hereafter reserved on any lease by a tenant in fee or for any life interest, or by any lease granted under any power, and all rents-charge and other rents, annuities, pension, dividends, moduses, compositions, and all other payments of every description, made payable or coming due at fixed periods under any instrument that is hereafter executed, or (being a will or testamentary instrument) that comes into operation hereafter, shall be apportioned in such manner that on the death of any person interested in any such rents, annuities, pensions, dividends, moduses, compositions, or other payments as aforesaid, or in the estate, fund, office, or benefice from or in respect of which the same are issuing or derived, or on the determination by any other means of the interest of any such person, the person and his or her personal representatives, or assignees shall be entitled to a proportion of such rents, annuities, pensions, dividends, moduses, compositions, and other payments according to the time which has elapsed from the commencement or last period of payment thereof respectively (as the case may be), including the day of the death of the person or of the determination of his or her interest, all just allowances and deductions in respect of charges on such rents, annuities, pensions, dividends, moduses, compositions, and other payments being made; and that every such person, his or her personal representatives, and assignees, shall have the same remedies for recovering such apportioned parts of the said rents, annuities, pensions, dividends, moduses, compositions, and other payments, when the entire portion of which such apportioned parts form part becomes due and payable, and not before, as he or she or they would have had for recovering such entire rents, annuities, pensions, dividends, moduses, compositions, and other payments if entitled thereto, but so that persons liable to pay rents reserved by any lease or demise, and the land comprised therein, shall not be resorted to for such apportioned parts specifically as aforesaid, but the entire rents of which such portions shall form a part shall be received and recovered by the person who but for this section would have been entitled to such entire rents; and such portions shall be recoverable in any action from such person by the party entitled to the same under this Act.

Saving effect of express contracts

13 Sections 11 and 12 do not apply to any case in which it is expressly stipulated that no apportionment shall take place, or to annual sums made payable in policies of assurance.

All grants and conveyances to be good, without attornment of tenants

14 All grants and conveyances heretofore or hereafter made of any real estate or rents, or of the reversion or remainder of any land, are good and effectual without any attornment of any tenant of any such land out of which such rent shall be issuing, or of the particular tenants on whose particular estates any such reversions or remainders shall and may be expectant or depending, as if their attornment had been had and made; but no such tenant shall be prejudiced or damaged by payment of any rent to any such grantor, or by breach of any condition for nonpayment of rent, before the notice is given to the tenant of such grant by the grantee.

Persons holding over land after expiration of lease to pay double yearly value

15 In case any tenant for any term of life, lives, or years or other person who comes into possession of any land by, from, or under, or by collusion with the tenant, wilfully holds over any land after the determination of any such term, and after demand made and notice in writing given for delivering the possession thereof by the landlord or lessor, or the person to whom the remainder or reversion of such land belongs, or that person’s agent thereunto lawfully authorized, then and in such case the person so holding over shall, for and during the time he or she holds over or keeps the person entitled out of possession of the land pay to the person kept out of possession, or that person’s personal representatives or assignees, at the rate of double the yearly value of the land so detained, for so long time as the same are detained, to be recovered in any court of competent jurisdiction.

Tenants holding premises after time they notify for quitting them to pay double rent

16 In case any tenant gives notice of his or her intention to quit the premises by him or her holden at a time mentioned in the notice, and does not deliver up possession thereof at such time, then the tenant or his or her personal representatives shall thenceforward pay to the landlord double the rent or sum which he or she shall otherwise have paid; to be levied and recovered at the same times and in the same manner as the single rent or sum before giving such notice could be levied or recovered; and such double rent or sum shall continue to be paid during all the time such tenant shall so continue in possession.

Definitions for purposes of sections 18 to 28

17 In sections 18 to 28:

“landlord” includes the lessor, owner, the person giving or permitting the occupation of the premises in question, and the person entitled to possession, and his or her heirs, assignees and legal representatives;

“tenant” includes an occupant, a subtenant, undertenant, and his or her assignees and legal representatives.

Landlord may apply to Supreme Court

18 (1) In case a tenant, after the lease or right of occupation, whether created in writing or verbally, has expired, or been determined, either by the landlord or by the tenant, by a notice to quit or notice under the lease or agreement, or has been determined by any other act whereby a tenancy or right of occupancy may be determined or put an end to, wrongfully refuses, on written demand, to go out of possession of the leased land, or the land that the tenant has been permitted to occupy, the landlord may apply to the Supreme Court

(a) setting out in an affidavit the terms of the lease or right of occupation, if verbal;

(b) annexing a copy of the instrument creating or containing the lease or right of occupation, if in writing;

(c) if a copy cannot be annexed by reason of it being mislaid, lost or destroyed, or of being in possession of the tenant, or from any other cause, then annexing a statement setting forth the terms of the lease or occupation, and the reason why a copy cannot be annexed;

(d) annexing a copy of the demand made for delivering possession, stating the refusal of the tenant to go out of possession, and the reasons given for the refusal, if any; and

(e) any explanation in regard to the refusal.

(2) This section extends and shall be construed to apply to tenancies from week to week, from month to month, from year to year, and tenancies at will, as well as to all other terms, tenancies, holdings or occupations.

(3) An application under subsection (1) shall be commenced at a registry of the Supreme Court located in the judicial district where the land is situated.

Court to appoint time and place of inquiry, etc.

19 If after reading the affidavit it appears to the court that the tenant wrongfully holds and that the landlord is entitled to possession, the court shall appoint a time and place to inquire and determine whether the person complained of was a tenant of the complainant for a term or period which has expired, or has been determined by a notice to quit or otherwise, whether the tenant holds possession against the right of the landlord and whether the tenant has wrongfully refused to go out of possession, having no right to continue in possession.

Notice in writing of inquiry

20 (1) Notice in writing of the time and place appointed under section 19 shall be served by the landlord on the tenant or left at the tenant’s residence or place of business at least 5 days before the day appointed, if not more than 32 km from the tenant’s residence or place of business and one day in addition for every 32 km above the first 32, reckoning any broken number above the first 32 as 32 km.

(2) A copy of the affidavit on which the appointment was obtained, and of the papers attached to it shall be annexed to the notice.

Court to issue writ of possession

21 (1) If at the time and place appointed under section 19 the tenant, having been notified as provided, fails to appear, the court, if it appears to it that the tenant wrongfully holds, may order a writ to issue to the sheriff, commanding him or her to place the landlord in possession of the premises in question.

(2) If the tenant appears at the time and place, the court shall, in a summary manner, hear the parties, examine the matter, administer an oath or affirmation to the witnesses adduced by either party, and examine them.

(3) If after the hearing and examination it appears to the court that the case is clearly one coming under the true intent and meaning of section 18, and that the tenant wrongfully holds against the right of the landlord, then it shall order the issue of the writ under subsection (1) which may be in the words or to the effect of the form in the Schedule; otherwise it shall dismiss the case, and the proceedings shall form part of the records of the Supreme Court.

Other rights and remedies of landlords not prejudiced

22 Sections 18 to 21 do not prejudice or affect any other right or right of action or remedy that landlords may possess in any of the cases provided for.

Style of cause

23 Proceedings under sections 18 to 21 shall be commenced at a registry of the Supreme Court located in the judicial district where the land is situated.

Service

24 Service of all papers and proceedings under sections 18 to 21 shall be properly effected if made as required by law in respect of writs and other proceedings in actions for the recovery of land.

Landlord may apply to registrar of Supreme Court

25 (1) In case a tenant

(a) fails to pay rent within 7 days of the time agreed on, or

(b) makes default in observing any covenant, term or condition of the tenancy, the default being of a character as to entitle the landlord to enter again or to determine the tenancy,

and wrongfully refuses or neglects, on demand made in writing, to pay the rent or to deliver the premises leased, which demand shall be served on the tenant or on some adult person on the land or, if vacant, be affixed to the dwelling or other building on the land, or on some portion of the fences, the landlord or the landlord’s agent may apply to the registrar of the Supreme Court on affidavit

(c) setting forth the terms of the lease or occupancy,

(d) the amount of rent in arrears, and the time for which it is in arrears,

(e) producing the demand made for the payment of rent or delivery of the possession, and stating the refusal of the tenant to pay the rent or to deliver up possession, and the answer of the tenant, if an answer was made, and

(f) setting forth that the tenant has no right to set off or the reason for withholding possession, or setting forth the covenant, term or condition in performance of which default has been made, and the particulars of the forfeiture,

and on filing of the affidavit, the registrar shall issue a summons calling on the tenant, 3 days after service, to show cause why an order should not be made for delivering up possession of the premises to the landlord, and the summons shall be served in the same manner as the demand.

(2) An application under subsection (1) shall be commenced at a registry of the Supreme Court located in the judicial district where the land is situated.

Procedure on hearing and on enforcement of order for possession

26 (1) Subject to subsection (3), on return of the summons, the court shall, if the tenant appears, hear the parties on the evidence they may adduce on oath, and if the tenant, having been served as provided, does not appear, proceed in the tenant’s absence and make an order, either to confirm the tenant in possession or to deliver possession to the landlord, as the facts of the case warrant.

(2) In case an order is made for the tenant to deliver possession, and the tenant refuses, then the sheriff shall, with assistance as required, proceed under the order to eject and remove the tenant, and the tenant’s goods.

(3) If a tenant, in case the default is for nonpayment of rent, before enforcement of the order, pays the arrears and all costs, the proceedings shall be stayed and the tenant may continue in possession of the former tenancy.

(4) If the premises are vacant, or the tenant is not in possession, or if in possession and the tenant refuses, on demand made in the presence of a witness, to admit the sheriff, the latter, after a reasonable time has been allowed to the tenant or person in possession to comply with the demand for admittance, may force open any door in order to gain entrance, eject the tenant or occupant and give proper possession to the landlord or the landlord’s agent.

Costs

27 The court may award costs which may be added to the costs of the levy for rent.

Form of summons and order

28 The summons to be issued and the order required for possession may be in forms as provided by the Supreme Court Civil Rules.

Application of Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act (Canada) and rights of trustee and landlord

29 (1) In construing any word or expression occurring in this section, reference may be had to the interpretation section of the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act (Canada).

(2) Where a receiving order or an assignment is made against or by a lessee under the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act (Canada), the custodian or trustee, notwithstanding a condition, covenant or agreement in a lease, has the right to hold and retain the leased premises for a period not exceeding 3 months from the date of the receiving order or assignment, or until the expiration of the tenancy, whichever happens first, on the same terms and conditions as the lessee might have held the premises had no receiving order or assignment been made.

(3) If the lessee is a tenant of premises the tenancy of which is not determined by the making of a receiving order or assignment, the custodian or trustee may surrender possession at any time, and the tenancy shall terminate, but nothing shall prevent the trustee from transferring or disposing of a lease or leasehold property, or an interest of the lessee, for the unexpired term to as full an extent as could have been done by the lessee had the receiving order or assignment not been made. If the lease contains a covenant, condition or agreement that the lessee or his or her assignees should not assign or sublet the premises without the leave or consent of the landlord or other person, the covenant, condition or agreement shall be of no effect in case of such a transfer or disposition of the lease or leasehold property if the Supreme Court, on the application of the trustee and after notice of the application to the landlord, approves the transfer or disposition proposed to be made of the lease or leasehold property. Before the person to whom the lease or leasehold property is transferred or disposed of is permitted to go into occupation, that person shall deposit with the landlord a sum equal to 3 months’ rent, or supply to the landlord a guarantee bond approved by the court in a sum equal to 3 months’ rent, as security to the landlord that the person will observe and perform the terms of the lease, but the amount deposited or secured to the landlord shall not exceed the rent for the term assigned or sublet.

(4) The custodian or trustee has the further right, at any time before surrendering possession, to disclaim any lease, and his or her entry into possession of the leased premises and their occupation by him or her while required for the purposes of the trust estate shall not be evidence of an intention on his or her part to elect to retain the premises, nor affect his or her right to disclaim or to surrender possession under this section. If after occupation of the leased premises the custodian or trustee elects to retain them and after assigns the lease to a person approved by the court as by subsection (3) provided, the liability of the trustee and of the estate of the debtor is, subject to the provisions of subsection (5), limited to the payment of rent for the period of time during which the custodian or trustee remains in possession of the leased premises for the purposes of the trust estate.

(5) The landlord has a preferred claim against the estate of the lessee for arrears of rent not exceeding 3 months’ rent accrued due prior to the date of the receiving order or assignment, together with all costs of distress properly made before the date in respect of the rent hereby made a preferred claim.

(6) The landlord may prove as a general creditor for

(a) all surplus rent accrued due at the date of the receiving order or assignment; and

(b) any accelerated rent to which he or she may be entitled under his or her lease, not exceeding an amount equal to 3 months’ rent.

(7) Except as aforesaid, the landlord is not entitled to prove as a creditor for rent for any portion of the unexpired term of the lease, but the trustee shall pay to the landlord for the period during which the trustee or the custodian actually occupies the premises from and after the date of the receiving order or assignment a rental calculated on the basis of the lease and payable in accordance with its terms, except that any payment already made to the landlord as rent in advance in respect of that period, and any payment to be made to the landlord in respect of accelerated rent, shall be credited against the amount payable by the trustee for that period.

(8) The landlord is not entitled to distrain the goods of the lessee after the date of the receiving order or assignment, and all goods distrained before that date shall on demand be delivered by the person holding them to the custodian or trustee.

(9) Nothing in this section shall render the trustee personally liable beyond the assets of the debtor in the trustee’s hands.

Schedule

Form 1

Writ of Possession

The Supreme Court of British Columbia

To the Sheriff for ……………………………………..

The Supreme Court of British Columbia, by its order dated ……………………………. [month, day, year] made under the Commercial Tenancy Act, on the complaint of ………………………………………………………… against ………………………………………………, ordered that …………………………………..was entitled to the possession of …………………………………………, in your county, and ordered that a writ should issue accordingly [if the tenant is ordered to pay costs, insert here the following: and also ordered and directed that ……………………………….. should pay the costs of the proceedings under the Act, assessed by the court at $………………………]:

Therefore, we command that, without delay, you cause …………………………………….. to have possession of the land and premises.

[If the tenant is ordered to pay costs, insert here the following: And we also command that, out of the goods of ………………………………………… in your county, you levy $ ………………………, being the costs assessed by the court and deposit that money in court immediately after carrying out this writ.]

And further that you promptly advise the court of the manner you carry out this writ, and bring this writ.

Witness ………………………………, judge of the court at …………………….., on ……………….. [month, day, year].

……………………………………………….

Registrar

Form 2

Notice to Tenant

To ……………………………………. [Name of tenant]

I give you notice to deliver up possession of the premises ………………………………. [Identify the premises] which you hold of me as tenant, on ……………………., [month, day, year].

Dated ………………………….. [month, day, year].

……………………………………………….

Landlord

Form 3

Notice to Landlord

To ……………………………… [Name of landlord]

I give you notice that I am giving up possession of the premises ……………………….. [Identify the premises] which I hold of you as tenant, on ……………………. [month, day, year].

Dated ………………………. [month, day, year].

………………………………………

Tenant

Copyright (c) Queen’s Printer, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

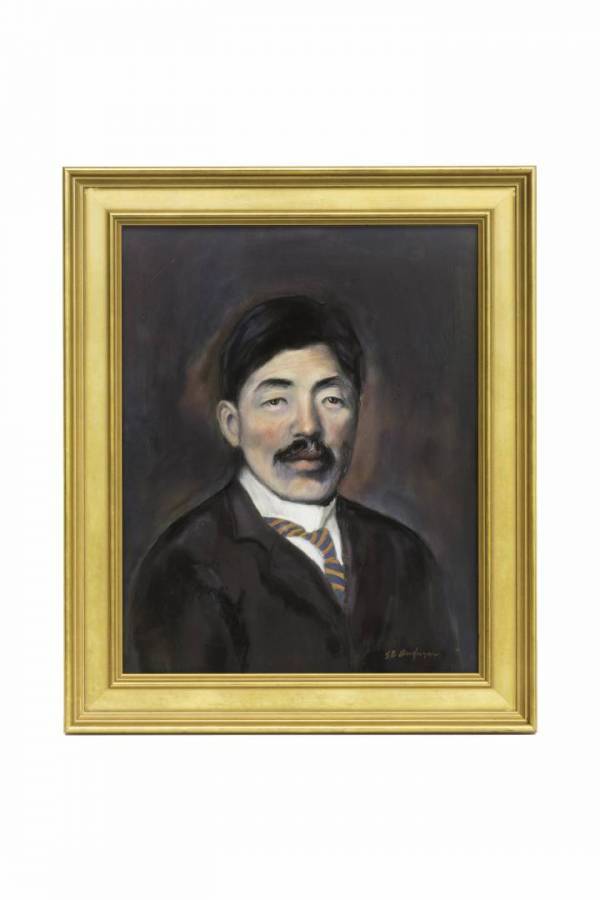

Samuel Hayakawa, Minoru Kobayashi, Hide Hyodo Shimizu and Edward Banno (left to right) at Parliament to campaign for voting rights. Nikkei National Museum, 2000.14.1.1.

Samuel Hayakawa, Minoru Kobayashi, Hide Hyodo Shimizu and Edward Banno (left to right) at Parliament to campaign for voting rights. Nikkei National Museum, 2000.14.1.1. Kartar Singh, Kapoor Singh, Dr. Durai Pal Pandia, and Mayo Singh were community leaders who would help win the franchise in 1947. Sarjit K. Siddoo and Hugh Johnston (author of Jewels of the Qila).

Kartar Singh, Kapoor Singh, Dr. Durai Pal Pandia, and Mayo Singh were community leaders who would help win the franchise in 1947. Sarjit K. Siddoo and Hugh Johnston (author of Jewels of the Qila).